Introduction — The Age When Photography’s “Magic” Arrived in Japan

In the mid-19th century, the art of photography, brought over from the West, appeared to the Japanese people of that era as nothing short of magic. Human faces and landscapes could be burned directly onto paper, preserved exactly as they were. This reproduction of “reality” — so utterly different from paintings or woodblock prints — filled people with astonishment, and even a sense of awe.

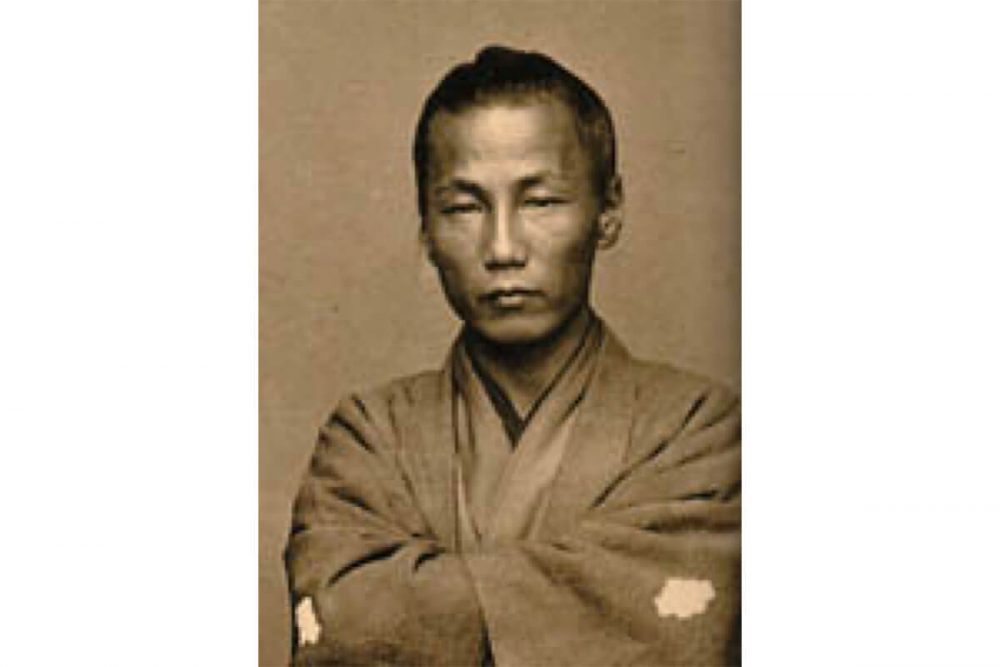

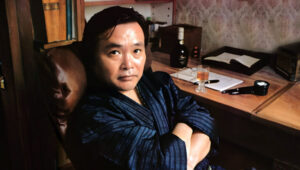

Standing at the very forefront of that era was a man who mastered photography through self-study alone, captured some of the most iconic figures of the Bakumatsu period — including Sakamoto Ryoma and Takasugi Shinsaku — on camera, and ultimately went to the battlefield as Japan’s first war photographer. His name was Ueno Hikoma, proprietor of a photography studio in Nagasaki.

He was a chemist, an educator, and a war photographer all at once. Tracing the life of this multifaceted individual reveals a universal mindset that resonates even today: the conviction to seize new technology with one’s own hands, no matter the obstacle.

Who Was Ueno Hikoma? — A Young Chemist Who Called Nagasaki Home

Ueno Hikoma was born in 1838 (Tenpō 9) in Nagasaki. His father was a scholar of Dutch learning, and Hikoma grew up in an environment steeped in Western knowledge from an early age. The city of Nagasaki itself played a crucial role. Even during Japan’s era of national seclusion, Western culture continued to flow in through the trading post at Dejima, making this city one of the few places in Japan where the “air of the outside world” could truly be breathed.

Hikoma studied chemistry and Dutch learning, and eventually encountered the art of photography around 1857 (Ansei 4). At the time, photography had only recently arrived from the West and was still cutting-edge technology. There were virtually no specialists in Japan, and almost no textbooks on the subject existed in the Japanese language.

Yet Hikoma was undeterred. He gathered every Western book and chemistry text he could find and, relying on written sources alone, set about acquiring the knowledge he needed — the chemicals, the equipment, the entire technical process of taking photographs.

Self-Teaching Photography from Books Alone — The Grueling Process of Trial and Error

Just how difficult this self-taught journey was becomes clear when one imagines the circumstances of the time. There was no internet, no video tutorials. With no Japanese-language guides to rely on, Hikoma wrestled with chemical formulas and attempted to synthesize the necessary compounds with his own hands.

Perhaps the most famous episode involves his attempt to obtain ammonia.

Certain chemical agents were indispensable for developing and fixing photographs, but in Japan at the time, they simply could not be purchased on the open market. So Hikoma turned to a solution that was quintessentially the kind of thing a chemistry-obsessed young man would devise: he buried meat-bearing cattle bones in the ground and allowed them to rot. Drawing on his chemical knowledge that ammonia is released during the decomposition of organic matter, he set the experiment in motion.

But there was a severe side effect. The overwhelming stench emanating from the decomposing bones spread through the neighborhood, and he was eventually reported to the local magistrate’s office. In modern terms, it might be likened to a young man conducting bizarre experiments in his backyard and getting reported to the authorities.

This story is sometimes told as a comic anecdote, but its essence is anything but comic. If you can’t obtain what you need, make it yourself. If there is no precedent, blaze the trail yourself. That spirit embodies exactly the attitude one should bring to mastering a new technology.

After years of struggle, Hikoma opened the Ueno Photography Studio in 1862 (Bunkyū 2), on the banks of the Nakashima River in Nagasaki — one of the pioneering photography studios in all of Japan.

Sakamoto Ryoma, Takasugi Shinsaku — The Man Who Photographed the Heroes of the Bakumatsu

The era in which Ueno’s studio opened coincided with one of the most turbulent periods in Japanese history. Nagasaki, as a gateway to the West, was also a politically vital city where anti-shogunate activists moved freely.

Against this backdrop, Hikoma’s camera continued to capture historic moments.

It is widely believed that Sakamoto Ryoma was photographed at Ueno’s studio, and that iconic image of Ryoma — standing upright, one hand tucked into his chest, his gaze firm and resolute — is a living testament to that legacy. Takasugi Shinsaku and other heroes of the Bakumatsu era are also said to have been photographed within those walls.

In an age when photography was just beginning to take on the role of “preserving one’s face for posterity,” Ueno’s studio became, in a very real sense, a witness to history. The reason we can know the faces of Bakumatsu figures today is precisely because pioneers like Hikoma were there with their cameras.

Publishing Chemistry Texts — The Spirit of a Scientist Who Refused to Hoard Knowledge

What sets Ueno Hikoma apart from being merely a studio photographer is his publication of chemistry texts on the art of photography.

The knowledge he had worked so hard to acquire, Hikoma shared openly and without reservation. He published detailed written works explaining how to formulate the necessary chemical agents, how the developing process worked, and how to handle equipment — laying it all out for anyone who wished to learn.

The significance of this act cannot be overstated. Knowledge, kept secret, becomes a commercial advantage. By guarding the mysteries of photography, he could have kept competitors at bay. But Hikoma chose otherwise.

This was likely because, deep within him, there burned a sense of mission — not simply as a merchant seeking to maximize profit, but as a scientist and educator who wanted to see photography take root across Japan as a whole. He found greater value in broadening the reach of this new expressive technology than in protecting his own business interests.

It is an ethos that prefigures the modern open-source movement, or the practice of scientists freely publishing their research findings. Paving a road you struggled to open, and leaving it smoothly laid for those who come after you — this kind of generosity of spirit is precisely what elevates Ueno Hikoma above the status of a mere “photographer.”

Japan’s First War Photographer — The Satsuma Rebellion and a Quiet, Deliberate Gaze

In 1877 (Meiji 10), the Satsuma Rebellion erupted — a violent clash between the Satsuma forces led by Saigo Takamori and the army of the Meiji government. It was to this battlefield that Ueno Hikoma traveled as Japan’s first war photographer.

This was a landmark moment in both the history of Japanese photography and the history of journalism. The act of recording a battlefield with a camera was entirely without precedent at the time, and both its significance and its dangers were immeasurable.

Yet the war photographs Hikoma left behind have one striking characteristic.

Almost no images of the dead appear among them.

War photography, as we know from images produced in later eras, often records corpses and scenes of carnage directly — justified, at times, as necessary for conveying the reality of war. But Hikoma made a deliberate choice not to do this.

Why?

No definitive record remains to answer the question, but we can reflect on what lay behind that gaze. From the Bakumatsu era through the Meiji Restoration, Hikoma had photographed countless people. He knew better than anyone the tension and pride of a human being standing before a camera — the weight of a person’s existence. Those who had fallen on the battlefield were also, once, someone’s son, someone’s father, someone’s friend. A deep hesitation, and a profound sense of respect for those fallen figures — perhaps that is what lay behind Hikoma’s choice not to photograph the dead.

From another angle, this can also be read as an awareness of the power that photography holds. A camera appears to capture reality as it is, but in truth, reality is constructed through the choices of what to shoot and what to leave unshot. Hikoma may have instinctively understood the weight of that choice.

His photographs of the battlefield are quiet. The dead are absent. And yet, war is undeniably present. In the exhausted faces of those who survived, in the devastated land, in the objects left behind — through these, Hikoma sought to convey the true nature of war by other means.

The Spirit of Ueno Hikoma, Alive in the Modern World

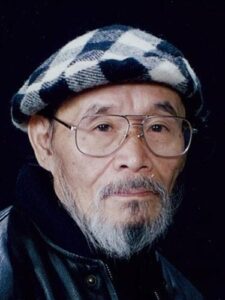

Ueno Hikoma passed away in 1904 (Meiji 37) at the age of 66.

The era he lived through was one of tumultuous transformation, as Japan shed its feudal shell and emerged as a modern nation-state. Photography itself underwent a parallel metamorphosis — from a curious novelty to a tool of journalism and artistic expression. And at the leading edge of all of it, Hikoma was always there.

There is much to learn from his life.

If the knowledge you need is unavailable, create it yourself. If there is no precedent, become the precedent. Do not hoard the knowledge you have acquired — open it to the next generation. And in all expression, embed ethics and a conscious gaze.

These are not lessons limited to the specific technology of photography. They are a mindset that applies to every person who dares to venture into a new field or take on a new technology.

Even in an age when cutting-edge technologies like AI and quantum computing are reshaping the world, the spirit of “the young man who rotted cattle bones to make his own chemicals from a book” resonates with surprising freshness.

Conclusion

When we look at a photograph of Sakamoto Ryoma, we see only Ryoma. But beyond that frame stands a single man who endured foul odors while making his own chemical compounds from scratch, was reported to the magistrate’s office, and still refused to give up — pressing the shutter again and again.

That man’s name was Ueno Hikoma.

Standing at the very starting point of Japanese photographic history, and remaining faithful — as a scientist, as an educator, and as a human being — to the end, the life of this remarkable individual reaches across time and poses a question to each of us:

Do you have the conviction, and the gaze, to capture your own new era on camera?

Reference: NHK “The Wisdom of Our Predecessors: Chie-Izu,” episode featuring Ueno Hikoma

コメント