Introduction: The Loss of a “Human Death”

Modern medicine has made remarkable progress. However, in the shadow of this advancement, aren’t we losing something precious?

In emergency medical settings, numbers and monitors represent a patient’s condition, and sometimes even family members cannot be present at the final moment. Death has become managed as data, measured quantitatively, and the once natural practice of “people dying with dignity” has become increasingly difficult.

One psychiatrist sounded the alarm about this situation and brought revolution to end-of-life care: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

The Problems Kübler-Ross Observed in Medical Settings

Death Reduced to Numbers, Humanity Left Behind

In 1960s America, advances in medical technology expanded the possibilities for saving lives, but at the same time, the psychological and spiritual needs of dying patients came to be neglected.

Hospitals prioritized efficiency, and patients were sometimes called by their room numbers or medical record numbers. Once terminal patients were determined to have “no more treatment options,” they tended to be avoided by medical staff. Death was viewed as a medical “failure,” and time to address the feelings of patients themselves and the grief of families was put on the back burner.

An Innovative Initiative Born from Crisis Awareness

Deeply troubled by this situation, Kübler-Ross began a groundbreaking initiative at Billings Hospital in Chicago: a workshop on “death and the dying process.”

This workshop provided a setting where medical students and healthcare professionals could engage in actual dialogue with terminal patients. With the patients’ consent, the content of these conversations was recorded and analyzed in detail. Through dialogues with approximately 200 terminally ill patients, Kübler-Ross systematically attempted to understand the psychology of those facing death.

The Five Stages Revealed in “On Death and Dying”

New Understanding Through a Qualitative Approach

While conventional medicine viewed “death” as a physiological phenomenon, Kübler-Ross reexamined the process of death from a qualitative perspective. She focused on the inner movements of human beings that cannot be expressed in numbers or data.

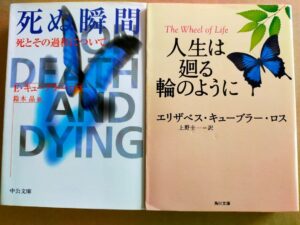

The result of her research was published in her book “On Death and Dying” (1969). The “five stages in the process of accepting death” presented in this book is still referenced worldwide as a foundational theory for end-of-life care.

What is the Five-Stage Model?

The five stages proposed by Kübler-Ross are as follows:

Stage One: Denial

“This can’t be happening” or “There must be some mistake”—this is the stage where people reject the fact that they are facing death. As a defensive reaction to the sudden announcement of death, a psychological state emerges where reality cannot be accepted.

Stage Two: Anger

When denial can no longer be maintained, anger wells up: “Why me?” “This is unfair.” Anger may be directed at medical staff, family, or God.

Stage Three: Bargaining

“If I could just live a little longer, I would do anything”—this is the stage of attempting to negotiate with God or fate. People try to postpone death by promising good deeds or offering prayers.

Stage Four: Depression

Understanding that death is an unavoidable reality, people sink into deep sadness. They realize the magnitude of what they will lose and are overcome by despair.

Stage Five: Acceptance

Finally, this is the stage where people quietly accept their death. They reach a peaceful state of mind, transcending fear and anger.

Proper Understanding of the Model

However, this five-stage model is not a rigid framework suggesting that all patients necessarily progress through these stages in this order. People may move back and forth between stages, or some may not experience certain stages at all. What Kübler-Ross wanted to convey was that there are diverse and complex processes in the hearts of those facing death, and the importance of understanding and empathizing with these processes.

Transforming Approaches to Terminal Patients

The Power of Listening

The greatest change that Kübler-Ross’s research brought to medical settings was the attitude of “listening to patients’ voices.”

Until then, medical professionals were figures who unilaterally explained to patients and gave instructions. However, Kübler-Ross revealed that what dying people need most is someone who will acknowledge their fears, sadness, and anger.

In the workshops, medical students repeatedly experienced simply listening to patients. They learned the value not of speaking about diagnosis or treatment, but of sincerely listening to what patients were feeling and wanting to communicate in the moment.

Recognizing the Role of Family

Kübler-Ross’s research also highlighted the importance of family in the terminal stage.

Due to the streamlining of medical care, the time families could spend with patients tended to be limited. However, for those who are dying, time with loved ones is more precious than anything. The opportunity to say goodbye, express gratitude, and share memories is a crucial process that brings closure to a person’s life.

Through Kübler-Ross’s advocacy, the importance of family-centered care in end-of-life medicine came to be recognized.

Implications for Today: Development of Hospice Care and Palliative Medicine

The Birth of the Hospice Movement

Kübler-Ross’s research had a significant impact on the development of hospice care. Combined with the modern hospice movement begun by Cicely Saunders in the United Kingdom, the idea of “providing high-quality care to patients for whom cure is not possible” spread throughout the world.

Hospices address not only pain management but also patients’ psychological, social, and spiritual needs. Systems are established with multidisciplinary teams to support patients in spending their final days as themselves.

The Spread of Palliative Care

Currently, it is recommended to introduce palliative care not only in the terminal stage but from the time of diagnosis with serious illnesses such as cancer. This too is an extension of the philosophy Kübler-Ross presented: “responding to patients’ holistic suffering.”

According to the WHO definition, palliative care is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.”

What We Can Do to Reclaim Death with Dignity

Not Treating Death as Taboo

In Japan, speaking about death has traditionally been considered bad luck. However, death is something everyone must eventually face. Discussing what kind of end we want while we are healthy is not a negative thing at all.

Rather, by sharing intentions in advance, families won’t struggle with decisions when the time comes, and care in the form desired by the individual becomes more achievable.

Utilizing Advance Care Planning (ACP)

In recent years, the importance of Advance Care Planning (ACP), also called “life meetings,” has been recognized. This is a process in which the individual, family, and healthcare professionals repeatedly discuss future medical care and treatment, and share the individual’s wishes.

Where do you want to spend your final days? What treatments do you want, or not want? Openly discussing these matters is the first step toward realizing a death that is true to who you are.

Communication Between Medical Professionals and Patients/Families

As Kübler-Ross emphasized, what matters most in the terminal stage is honest, compassionate communication.

Medical professionals are called upon to empathize with the emotions of patients and families and to engage in dialogue with sufficient time. On the other hand, patients and families must also have the courage to express their feelings and wishes without hesitation.

Conclusion: Reconsidering the Meaning of Death

Kübler-Ross’s “On Death and Dying” is not simply a medical text. It is a book that asks us about the “meaning of death” that modern society has been losing sight of.

Death is not defeat but the natural conclusion of life. And that process is unique and irreplaceable for each individual.

No matter how much medical technology advances, death itself cannot be avoided. However, we can choose how we face death. Maintaining dignity, surrounded by loved ones, spending our final moments as ourselves—this is a right everyone deserves and a value that society as a whole should support.

The dialogue that Kübler-Ross began continues today. Speaking about death is actually also speaking about life. How to live our limited lives, what to value, and what thoughts we want to leave behind at the end.

When we face these questions, perhaps we finally become aware of the true meaning of life.

コメント