Introduction: February 1998 — The End of an Era

In February 1998, Takahashi Chikuzan, a towering figure in the world of Tsugaru shamisen, passed away at the age of 84. His death was not simply the loss of one musician. It was the moment the world lost a living witness to a music born from the very soil of Tsugaru — a music that was, in every sense, the sound of survival itself.

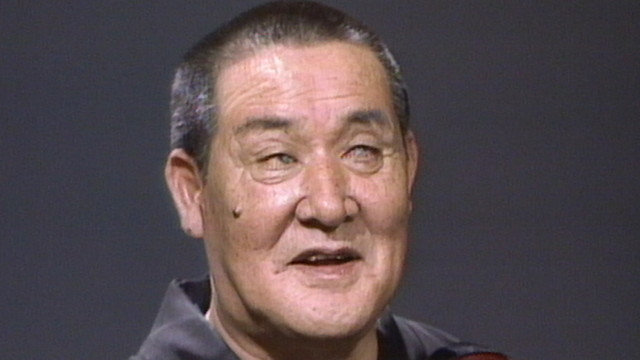

Anyone who has ever heard Chikuzan play will understand. The raw, searing tone of his shamisen transcended the boundaries of folk music, carrying within it the weight of human karma and suffering. The documentary The Final Stage: Tsugaru Shamisen Master Takahashi Chikuzan’s Challenge, produced near the end of his life, drew on a deathbed interview and testimonies from those close to him to trace the message Chikuzan was determined to leave behind.

This article, drawing on that documentary, explores the life and philosophy of Takahashi Chikuzan — and deciphers the “musical testament” he carved into existence alongside the storms and snowdrifts of Tsugaru.

Who Was Takahashi Chikuzan? — The Origins of a Traveling Performer Born of Poverty and Blindness

Takahashi Chikuzan was born in 1910 in Kaitamachi, Higashi-Tsugaru District, Aomori Prefecture. As a young child, he contracted smallpox, which left him nearly blind, and he was forced into a life of kadozuke — traveling from village to village as a blind street performer, playing shamisen at people’s gates in exchange for a few coins or a meal.

Kadozuke was a life balanced on the edge of humiliation, a daily struggle to survive Tsugaru’s brutal winters alone on the road. Yet it was precisely this existence that formed the very roots of Chikuzan’s music.

<u>His shamisen was not learned as an “art form” — it was absorbed into his body as a means of staying alive.</u> This distinction is decisive. Before any question of technical skill, the sound itself carried an urgency and a gravity that could only come from that kind of life.

According to those who knew him, Chikuzan often said: “My shamisen was made by the cold of Tsugaru and the emptiness in my stomach.” This was no metaphor. It was the literal truth.

A Life That Mirrored Tsugaru’s History of Snow and Hardship — How an Era of Suffering Became Sound

The era Chikuzan lived through was one of turbulence for Tsugaru as well. The great crop failures of the early Showa period, the Pacific War, postwar poverty and reconstruction — the Tsugaru region was among the last in Japan to benefit from modernization, and its people’s suffering ran correspondingly deep and long.

Through all of it, Chikuzan survived with nothing but his shamisen. He walked snowy roads from village to village, plucking the strings in the freezing cold. Those experiences gave his music an irreplaceable quality — a realness that could not be manufactured.

In the documentary, a longtime acquaintance offers this testimony: “Chikuzan’s shamisen wasn’t something you could judge as skilled or unskilled. Listening to it, something in your chest just ached. It sounded like a Tsugaru winter.”

“It sounded like a Tsugaru winter.” That phrase, I believe, cuts closer to the essence of Chikuzan than any music criticism ever could. Not a sound crafted through technique, but a sound ground out through the act of living. That was the shamisen of Takahashi Chikuzan.

The “Challenge” of His Final Years — Why Did Chikuzan Keep Taking the Stage Past the Age of 80?

Chikuzan first became widely known in the 1960s. The “blind traveling performer” who had lived on the margins of Tsugaru suddenly appeared on stages in Tokyo and stunned audiences who had never heard anything like him.

But his truest “challenge” came in his later years. Even past the age of 80, Chikuzan continued to perform. Even when his fingers lost their freedom of movement, even when the brilliance of his earlier playing had faded, he refused to stop.

When asked why he still played, Chikuzan answered in his final interview: “If I stop playing, there will be no proof that I was ever here.”

These words carry enormous weight. They speak not of artistic self-expression, but of something deeper — music as proof of existence itself. A man who had lived poor, blind, and on the margins of society could only inscribe the fact of his presence in the world through the act of playing. That desperation was what drove his aging body onto the stage, again and again, until the very end.

According to the documentary’s production staff, in his final years Chikuzan needed a long time to prepare in the wings before each performance. He would grip his bachi (plectrum) with trembling hands, breathing slowly and deeply. But the moment he stepped out onto the stage, his expression transformed. “When Chikuzan-san stepped out there,” one staff member recalled, “it was as if something else had taken over him entirely.”

What the Deathbed Interview Revealed — What Is “True Sound”?

There was a theme Chikuzan returned to again and again in his final interview: the question of what “true sound” really means.

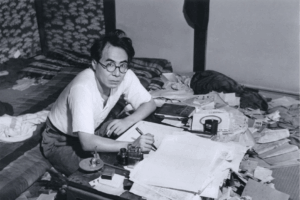

After Chikuzan brought Tsugaru shamisen to the world, the art form spread rapidly as a performing art. Competitions were established. Conservatories began teaching it as part of their curriculum. Young players emerged one after another. Some, in purely technical terms, surpassed Chikuzan himself.

Yet Chikuzan did not welcome this development without reservation. In the interview, he left behind these words: “There are plenty of children who have become skilled. But the shamisen of someone who has never known hunger is, somewhere, too clean.”

This was not a criticism of the younger generation. It was Chikuzan speaking with complete honesty about something he understood better than anyone. When suffering, hunger, and cold inhabit a sound, that sound acquires the power to shake the souls of those who hear it. Conversely, music polished purely through technique, without that lived experience, carries within it a kind of emptiness — a hollow space where something vital should be.

This statement is also a profound challenge to modern music education and the nature of art itself. “Life and art cannot be separated” — that idea is proven by the whole arc of Chikuzan’s existence.

What Takahashi Chikuzan Left Behind — A Legacy That Transcends the Genre of “Tsugaru Shamisen”

The influence Takahashi Chikuzan had on the world of shamisen is immeasurable. Before him, Tsugaru shamisen might have faded away before it was ever properly documented as a folk art tradition. By bringing that music onto formal stages, recording it, and spreading it across the country, Chikuzan ensured that a musical heritage was handed down to future generations.

But perhaps the more important legacy lies not in the music itself, but in the way he lived.

Never abandoning your own expression, no matter what circumstances surround you. Continuing to play despite poverty, despite blindness, despite old age. The meaning of that act — Chikuzan demonstrated it not through words, but through the sheer fact of his being.

In the documentary’s final scene, Chikuzan is shown playing his shamisen on what would be his last stage — and it left a deep impression on many viewers. Trembling fingers, yet an utterly unshakable expression on his face. In that image, the act of living and the act of expression had become perfectly, completely one.

Closing: What Chikuzan’s Sound Asks of Us

More than a quarter century has passed since Takahashi Chikuzan’s death. Yet the questions he left behind have not faded.

“What is true sound?” “What is expression?” “Where do living and art connect?” — these are universal questions that reach far beyond the frame of Tsugaru shamisen, touching anyone engaged in any form of creative work.

In an era where life has grown more convenient, more comfortable, and where technique can be acquired without hardship — precisely because of that, the life of Takahashi Chikuzan, who transformed his own poverty and loneliness and cold into the sound of a shamisen, forces us to reconsider something fundamental about what we are doing and why.

To anyone who has not yet seen the documentary The Final Stage: Tsugaru Shamisen Master Takahashi Chikuzan’s Challenge — I encourage you to seek it out. The old man captured on that screen is not simply the record of a great artist. He is one human being’s answer to the question of what it means to keep on living — and to never stop asking why.

Reference: Documentary — The Final Stage: Tsugaru Shamisen Master Takahashi Chikuzan’s Challenge (1998)

コメント