Cost of living: The shock of rising prices in Japan

Cost of living: The shock of rising prices in Japan – BBC News

Cost of living: The shock of rising prices in Japan

As a child growing up in Japan, things very rarely seemed to get more expensive.

My favourite lunch was always available for a 500 yen coin ($3.90; £3.10) and it remained that way until 2021. The same for shoes or clothes, little changed.

I was taught to save, save and save, and repeatedly warned that the value of our family home had collapsed in the 1990s, when the property market crashed.

This painful financial loss meant my parents, and many others like them, were never able to sell their house again or upgrade it.

But when prices for everyday items don’t increase, people don’t actively spend money.

Companies, in turn, respond by not increasing salaries, which lowers consumer demand and prices further. When you cannot get a pay rise, you don’t rush out to go shopping very often.

Taken altogether, this slows an entire country’s economic growth – a vicious cycle Japan has been trapped in for decades.

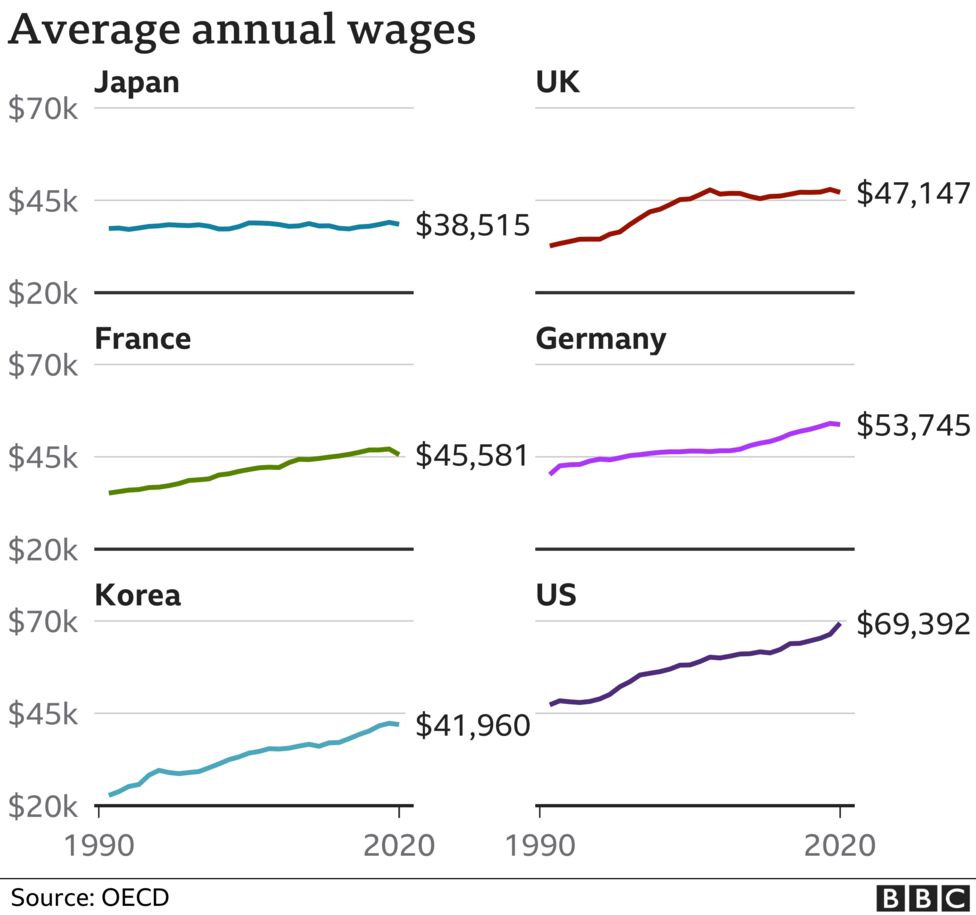

While many parts of Asia grew richer, Japan’s wealth stagnated. Japan’s gross domestic product per capita – the country’s economic output per person – remained stuck at the same level since the 1990s. By 2010, China had overtaken it as the world’s second-biggest economy.

For decades, with little success, the country’s central bank has tried to stimulate growth to get Japanese to “spend more, invest more, the wage goes up and the price goes up in tandem moderately”, explains Nobuko Kobayashi, a partner with EY-Parthenon.

In April, the benchmark measure for consumer prices rose 2.1%, enough that inflation this year is expected to finally hit the Bank of Japan’s 2% target, after three decades of essentially no rise at all.

However, the jump has nothing to do with domestic economic policy. It has been driven largely by higher import costs, a global increase in raw material and energy prices – pushed higher by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Ms Kobayashi even warns it could mark “the start of bad inflation, because wages have not gone up yet”. In fact, average salaries have hardly risen for over three decades, so things are about to get painful for shoppers.

While post-Covid there are many governments battling rising prices and a higher cost of living, it comes as a huge shock to Japan, where people have been used to decades of stable prices.

When the price of Japan’s everyday snack – umaibo – which was always priced at 10 yen ($0.075; £0.06) since its creation 43 years ago – went up by 20%, it sent a shockwave through the nation.

In a society which believes in sharing social burdens, increasing prices has become something of a cultural taboo.

So much so that Yaokin, the company which makes the popular snack, had to launch an ad campaign explaining why it had to increase the price.

But it was inevitable and one by one, everything from mayonnaise and bottled drinks to beer has become more expensive. According to Teikoku databank, prices for more than 10,000 food items are set to go up by an average of 13% this year.

生活費。日本における物価上昇の衝撃

日本で育った子供の頃、物事が高くなることはほとんどありませんでした。

私の好きなランチはいつも500円玉(3.90ドル、3.10ポンド)で食べることができ、それは2021年までそのままでした。靴や洋服も同じで、ほとんど変わりません。

私は、節約、節約、節約と教えられ、1990年代の不動産市場の暴落で実家の価値が暴落したことを何度も警告されました。

この痛ましい経済的損失により、私の両親や他の多くの人々は、再び家を売ったり、アップグレードしたりすることができなくなったのです。

しかし、日用品の値段が上がらないと、人々は積極的にお金を使うことはありません。

企業は給料を上げないことで対応し、消費者の需要と物価をさらに下げます。給料が上がらないと、急いで買い物に行くこともあまりありません。

このような悪循環は、日本が何十年にもわたって陥っている。

アジアの多くの地域が豊かになる一方で、日本の豊かさは停滞した。日本の一人当たりの国内総生産、つまり一人当たりの経済生産高は、1990年代から同じ水準にとどまっている。2010年には中国に抜かれ、世界第2位の経済大国となった。

EY-Parthenonのパートナーである小林伸子氏は、「数十年にわたり、日本の中央銀行は、日本人に『もっと消費し、もっと投資し、賃金も上がり、物価も適度に連動して上がる』ように成長を刺激しようとしてきましたが、あまり成功していません」と説明している。

4月の消費者物価指数(ベンチマーク)は2.1%上昇し、30年間まったく上昇しなかった今年のインフレ率がついに日銀の目標値である2%に達する見込みであるほどだ。

しかし、この上昇は国内の経済政策とは関係がない。輸入コストの上昇、原材料やエネルギー価格の世界的な上昇、パンデミックやウクライナ戦争による高騰が主な原因である。

小林氏は、「賃金はまだ上がっていないので、悪いインフレの始まりになるかもしれない」とさえ警告している。実際、平均給与は30年以上ほとんど上がっていないのだから、買い物客にとっては痛い目に遭おうとしているのだ。

コビト以降、多くの政府が物価の上昇や生活コストの上昇と戦っているが、何十年も安定した物価に慣れている日本にとっては大きなショックである。

43年前に誕生して以来、常に10円(0.075ドル、0.06ポンド)だった日本の日用品、うまい棒の価格が20%上昇したときは、日本中に衝撃が走りました。

社会的な負担を共有する社会では、値上げは文化的なタブーのようなものだった。

そのため、このスナックを製造しているヤオキンでは、値上げの理由を説明する広告キャンペーンを展開しなければならなかったほどだ。

しかし、それは避けられないことで、マヨネーズやペットボトル飲料、ビールなど、あらゆるものが次々と高価になっている。帝国データバンクによると、1万品目以上の食品が今年、平均13%値上がりすることになっている。(translated by me)

イギリスのBBCまでが指摘する事態に日本は陥っています。

その原因は何でしょう?

記事には、「輸入コストの上昇、原材料やエネルギー価格の世界的な上昇、パンデミックやウクライナ戦争による高騰が主な原因である。」と書かれていますが、それは間違いなのは明らかです。

そう、政策の失敗です。誰が見ても明らかです。

先日は、日銀の総裁が値上げは、国民が望んでいるなどと、とんちんかんな発言が話題になりましたね!

日本の軍事費を国民に換言すればという「東京新聞」のニュースも話題になりました。

防衛費倍増に必要な「5兆円」教育や医療に向ければ何ができる? 自民提言受け考えた:東京新聞 TOKYO Web (tokyo-np.co.jp)

選挙に行きましょう!

日本は変わらなければなりません。

コメント